Philosophy of religion essay

Introduction

Deontology is the philosophical pursuit of establishing what is right and what is wrong. More precisely, it is the pursuit of defining morality as what “ought to be”, hence, what is just. In ancient Greek, the word deon (δέον) is both used as a noun and a verb, being the present participle of dei (δέι). It is alternatively translated as “it is proper”, “it is necessary”, or “it is needed”, and its substantive meaning in English can be understood as “the duty” and “the best thing to be done”. Morality, hence, is the outcome of a deontological effort to find what is simultaneously the proper, necessary, and best conduct to adopt in life, and such effort must be guided by what we may call grounding cornerstones. In the following essay, I will take a comparative approach between German philosopher Immanuel Kant and Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky, and evaluate their deontological cornerstones.

Kant assesses that morality may be feasible only and necessarily under the condition of complete human freedom. Such freedom is rational and obtained through shredding processes that liberate man from external conditioning. Freedom is a prerequisite for morality, as it both disentangles man from empirical constrictions deterministically dictating what is right and wrong, and it rejects divine morality as a source of deontology because the conditioning by a superior being is the basis on which it is respected and revered.

On the other hand, Dostoevsky, who by writing novels and not philosophical volumes allows his views to emerge through his numerous and multifaceted characters, provides the idea that morality ought to be guided, put simply, by love. Throughout Dostoevsky’s novels, a very human “deontology of the heart” emerges, as contemporary philosopher Evgenia Cherkasovadiscusses in her book Dostoevsky and Kant: Dialogue on Ethics. My essay will partially rely on and draw from discussions emerging in this book.

Summary

Kant and Dostoevsky both share the idea that morality cannot and should not be determined by social milieu: the Russian writer staunchly opposes 19th-century philosophical and literary Naturalism, which scientifically argued, among other things, that moral corruption may be justified by environmental degradation. Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment, constantly lives the internal conflict of seeking morality while being unable to redeem himself. Whilst his poor social status leads him to commit horrific crimes, his soul and/or subconscious never free him from the grip of guilt, reminding him (and the reader) that no circumstance is destitute enough to free man from the awareness of good and evil. Similarly, Kant rejects the notion that morality can be induced a posteriori, given that if contingencies were to perpetually re-establish what is right and wrong, there would be no real, inherent freedom in the pursuit of an a-temporal morality. Both thinkers agree that right and wrong, good and bad, exist beyond situational human realities.

However, the novelist and the philosopher part ways in decreeing what, a priori, is the source of morality. Kant rejects the idea that God’s revelation establishes what is right and wrong, not because of what those commandments actually entail morally, but because the very adherence to them out of faith separates man’s choice to be moral from his freedom. His reverence to that morality is induced by fear of the afterlife, not by inherently free virtue.Thus, morality must come from within man’s rationality, and is deduced from autonomous reason. Contrarily, in his final novel and biggest masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky argues that in a world without God, or, more precisely, “with no immortality of the soul, […] everything is permitted”. This appears to be the same argument, but from the other side of the coin, namely, that fear of consequence guides human choice. However, throughout the book, this idea is debunked and, instead, is replaced with the notion that active, humble, laboured love, not fear, must be responsible for moral rectitude. Such love is manifested in the heart and responds to God’s deontology.

This divide leads to the schism between righteousness out of duty versus righteousness out of love and sets the basis for the philosophical clash between reason and heart. Idealism’s pure reason detaches the mind from the soul, and claims to human freedom based on alsosentiment lose legitimacy due to rationality’s pretence over truth.

This occurs only if freedom is understood as the polar opposite of faith. I will attempt to provide arguments for reconciling Kant and Dostoevsky’s deontologies, hoping to shed light on the fact that Kantian free, practical reason is completed with Dostoevsky’s view of faith, which rejects blind belief, posits love as the moral duty of humanity and also establishes freedom as a prerequisite to morality.

Freedom as the absolute autonomy of reason

In the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant assesses that, in order for there to be anything good, a “good will” (or good volition, or good intention) must lay at the basis of its pursuit. Briefly, man may accomplish anything worthy of rational, disinterested moral admiration if, and only if, the intentions set out before taking that action were good, regardless of whether, once accomplished, it actually turns out to be good. No quality, attribute, or fortune is good or bad per se: goodness as a virtue is measurable solely when it is still an unrealised volition of good-willing. Thus, moral actions are possible, according to Kant, when practical reason, the guarantor of good will, guides human choice.

Reason on its own is insufficient to provide men with the ability to make moral decisions: itmay be subjected to the satisfaction of rational self-interest or evil-doing, and optimal outcomes within these goals are undoubtedly achievable through cold reason, but areimmoral. On the other hand, emotional inclination alone, or “sympathy” to act morally, is also insufficient. Both pure reason and love are subject to contingency, thus to temptations and emotional volubility. If either were the motivators of morality, morality would beinconsistent and inconstant. Hence, actions of good will requires something beyond these two modes, which Kant identifies as duty.

Actions performed out of duty, contrary to actions satisfying self-interest or love, allow man to command upon himself what is practical because he rationally, but not manipulatively, respects a universal law which facilitates life for him and those he interacts with. What type of law? The one that respects the idea that “I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law”. Kant argues, “Since reason is required for the derivation of actions from laws, then will is only practical reason”. Yet, he continues, will is always dependent on contingent human subjectivity.

From this clash between the strength of pure reason and the weakness of contingent will (the heart’s impulses), a bolder, necessary imperative must guide choice for man to make morally good decisions, which are inherently practical. This categorical imperative for morality cannot be derived by empirical law – because it is by the definition of experience everchanging. Instead, the imperative must be unconditional. Thus, Kant introduces autonomy as a necessary prerequisite for truly fulfilling moral duty (i.e. respecting the categorical imperative). Unless autonomy guides will (“that is not absolutely good” because of human volition) in making a moral decision, man is not good-willing. The moral man is required to act with autonomy because of the inherent goodness of a law that is universally beneficial to all – not because there is self-interest in that decision. Kant so disqualifies holy law (God) from being the reason to act from duty, as the duty from faith comes at the price of external obligation (salvation), not the inherent goodness of will. Concludingly, freedom is the only way humanity can be moral. And from a deontological perspective, Kant declares agnosticism.

Freedom is the constant reminder of our ability to choose love

In the Russian writer’s literature, a different but parallel deontology emerges, and it too, as we shall see, serves itself of a “categorical imperative”: that of the heart, not of the mind.

One of Dostoevsky’s most elaborate and fundamental characters, Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment, is a man who has not lost his reason, but his soul. Contrary to Kant’s establishing that will is always subject to human volubility and reason may correct man’s erring, Raskolnikov commits a heinous murder when he is not yet a madman: his reasoning for murder appears sound, practical, and belongs to his cold, rational mind’s scheming. On the other hand, his soul and his heart will torment him forever (or until redemption) because the immorality he has drenched himself with persecutes him with guilt. In this sense, Dostoevsky’s “critique” of pure reason is much more severe than Kant’s, who corrects detached rationality with simple practicality. In opposition to pure idealism, the Russian proves that, humanly, to be morally good means to recognise love’s imperative over the mind’s. Additionally, although Raskolnikov is abysmally socially destitute, there is nothing which justifies his crime: for Dostoevsky too, morality cannot be subjective to human experience, and there must be a standard upheld a priori, which explains why in all possible contingencies, there is always a right or wrong.

Being a man of laboured faith, Dostoevsky posits that goodness relies on the mercy and love of God. But the conclusion is reached through an immense effort of casting doubt on man’s freedom and inherent ability to autonomously choose between good and evil – which, in the end is God’s biggest blessing.

Ivan, the middle Karamazov brother, is a young intellectual who wants to believe and live by a deontology of modern times. Suspecting that God does not exist, or rather, having no evidence that He does and thus rejecting not God himself, but His world, Ivan questions morality in absoluto. Who can truly assert that a higher harmony is even real, let alone just, when innocent suffering and useless corruption are widespread? Ivan asserts it will take humanity little time to realise the lie of the immortality of the soul, and soon after that – if not already as he speaks – morality will be unchained from the expectation of an eternal reward. Thus, while freedom from God is saddening and undesirable because it negates salvation, it is better than living by a construct constraining man’s autonomy, which is only a farce establishment of right and wrong, good and bad. However, Ivan is much less cynical, and much more soulful than he wishes to be. He rejects morality’s framework (God’s decree), but is unable to reject morality proper. Indeed, if everything became permissible when God died, then where else could morality have come from, if not God? Dostoevsky argues that this inextinguishable receptivity towards morality, lies in Ivan ability (and choice!) to love. Those who have lost that ability – such as Smerdyakov – are the only men truly void of morality.

In one of The Brothers Karamazov’s most famous passages, The Grand Inquisitor, Ivan recounts to Alyosha, his younger and pious brother, a poem about a Cardinal who encounters, reluctantly, Jesus Christ. The Cardinal represents the Church, its corruption, its pretence over justice, morality, and power. He tells Jesus to go away and never to return because the damage he has done to humanity by leaving scattered traces of good and bad has been finally corrected by the work of men of the Church like him, who “no longer serve this madness”. The madness the Cardinal refers to is believing man is actually capable of wholeheartedly, disinterestedly, and piously being good for the sake of God’s revelation – not His reward. Instead, the Church’s clever finding, is that, because man is faced with the agonising gift of freedom, he will always try to escape the burden of free choice. He won’t do good for the sake of good, even though he can freely decide to, because he needs a tangible purpose to guide him. So, man puts his heart at rest by delegating others with establishing the parameters of good and evil, and the Church has taken it upon itself to build morality to appease humanity’s otherwise inevitable self-destruction, caused by the existential loss cast by absolute freedom. Dostoevsky lets the Cardinal voice the 19th-century angst and rising popularity of atheism, but lovingly extinguishes it with the poem’s conclusion. Ivan ends the story of the Grand Inquisitor in a way that shows he has not yet lost all faith in unconditionalmorality – or, at least, in Dostoevsky’s understanding of morality with love being itscategorical imperative. Jesus allows the Cardinal to insult him and list all the reasons why he must not exist for the sake of humanity’s survival. At the end of the monologue, Jesus stands up, kisses the Cardinal, and leaves.

“God wants man’s free love so he would follow Him freely” says provocatively, but correctly, the Cardinal: what is the point of being good if there is no reward? The point is that free love requires no reward for it to be the source of unconditional morality. God’s gift of freedom allows man to be receptive towards the heart, which decrees the moral blessing of any decision. How could duties carried out of loveless, heartless rationales, be the source of anything, but immorality? Kant would argue that, because love is not a matter of will (with good will being the basis of any moral choice) but of feeling, if love were the categorical imperative, then the source of moral action would be arbitrary and inconsistent. However, this is precisely the point Dostoevsky makes: that while love is not a matter of will, it is a matter of choice, and when love becomes the categorical imperative of human morality, it is necessarily more good (because of the goodness which God imbues humble love with) than a unhuman rationalized practical reason. Indeed, Dostoevsky’s realistic implementation of moral philosophy in the dwellings of humane characters, proves that rationalism’s pretence over detached reason, is unattainable.

Morality is founded in practical reason, but its goodness comes from love. Why the source of such love is God, will be topic of another discussion, or, found in the reading of The Brothers Karamazov.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cherkasova, Evgenia. Dostoevsky and Kant: Dialogues on Ethics. Value Inquiry Book Series, v. 206. Amsterdam New York: Rodopi, 2009.

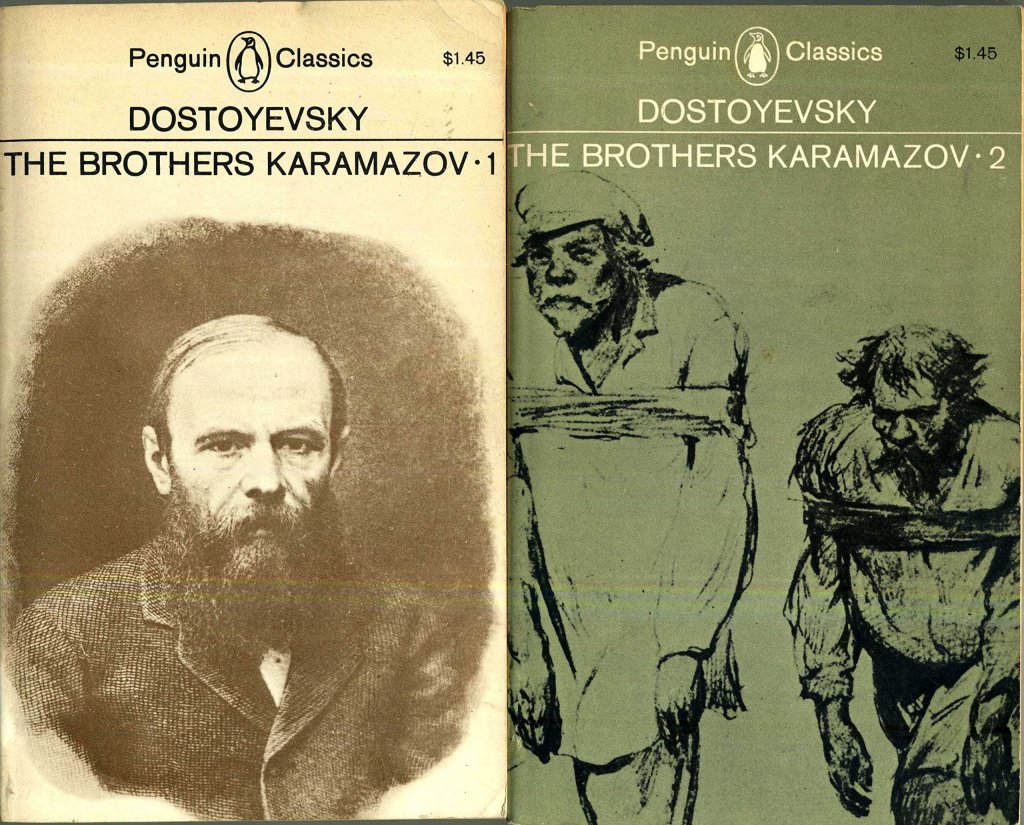

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The Brothers Karamazov. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Kant, Immanuel, Mary J. Gregor, and Jens Timmermann. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Revised edition. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Leave a comment