Short non-fiction creative story

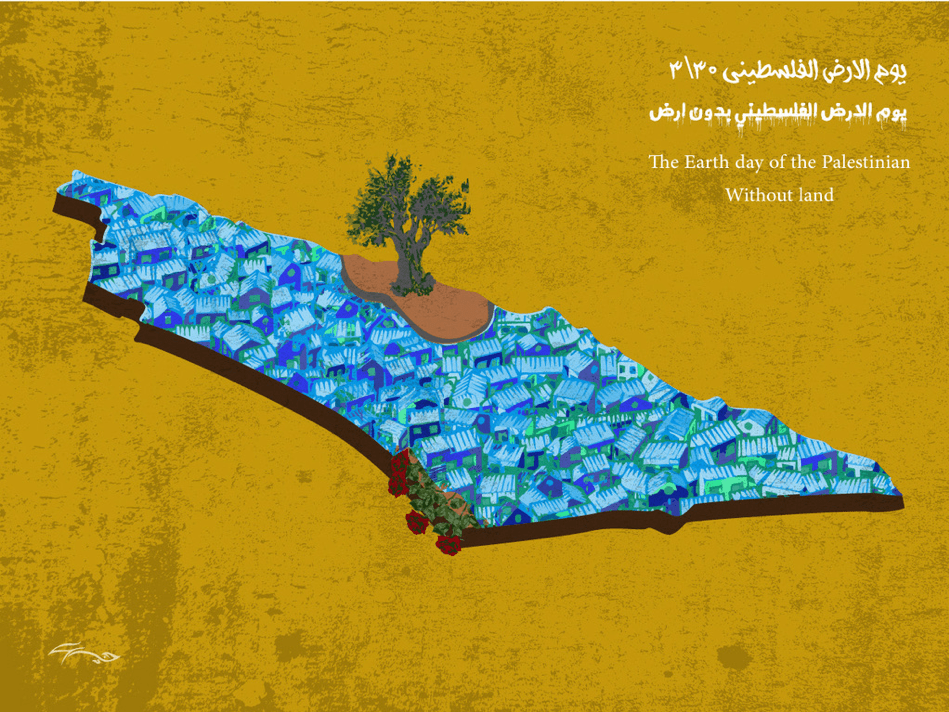

From the top of the orchard’s oldest olive tree, Raed could see the shining dome of Al-Aqsa mosque. He would climb up there when he felt overwhelmed, which happened often in his childhood. The house was always filled with children, homemade toys, laughter and cries. Raed’s parents were generous and caring people, who never failed to host a displaced family fleeing from Haifa or Akka. Because of that, Raed never felt lonely, and was never bored. But sometimes all the stories of people running away from their homes was too much for his little heart. That’s when he would run away into the garden to free his mind from such cruelty. He had never been to the places the refugees came from, but he was told that those cities, that sea from which they were expelled were historically, truthfully theirs. What haunted him the most in his childhood were the words of an elderly lady whose speaking was no longer clear because of old age, but who kept on repeating insistently, rhapsodically “The olives, the oranges, the pomegranates, my sea!” and then would fall in a dumbfound silence. Her sons wouldn’t listen to her because they had to deal with the future, figure out where to go live, how to start over their lives so suddenly. The lady, instead, knew she didn’t have lots of future ahead of her, and was tormented by the idea that all her past, the roots and the proof of her footprint on Earth, had been destroyed, torn from the ground, leaving no traces of her lifelong dedication to her Palestinian soil/soul.

Raed didn’t know why “The olives, the oranges, the pomegranates, my sea” always kept ringing in his ears, but when they did, he sprinted to his family’s garden and shouted to all the plants, trees, bushes “I won’t leave you, I won’t leave you!”. Then he hugged the olive tree, which was at the very center of the garden, and started to climb his way up until he reached the “chair branch”, the spot where Raed was most comfortable and where he would listen to the birds chirping. Raed missed his tree the most when it was wintertime: his mom didn’t want him to go out there, fearing he would catch a cold and that all the children in the house would get sick. But Raed couldn’t go more than two weeks without peaking at Al Aqsa’s dome from the olive tree’s branches. So, after morning prayer, when everyone went to bed, he would grab some dried fruits and a blanket and sneak out to the garden. He silently waited in the cold for sunrise to come and, when he started to see the frost sparkling on the dark green hills, he knew it would be a sunny day – and would be able to see clearly the uncontainable beauty of Al Aqsa. His family had an old photo of them in front of the Dome of the Rock hung in the living room, but Raed was just a baby when the photo was taken and couldn’t remember anything of that small, but fundamental, trip to Quds. He always heard his family speak about that day like a blessing from God. They had no longer been allowed to go to Quds because they lived after the ’67 border (West Bank). To go to Aqsa, they had been blessed with one of those special permits that one out of very few families get once in a while. Because of this, Raed’s imagination had built such an attachment to this turquoise, mosaic, golden mosque, that every time he prayed, he asked God to allow him to visit it at least once in his life.

Raed’s siblings all became successful or married and moved out of the historic house. Raed was never interested in pursuing higher education, he just wanted to tend to the garden and preserve the heritage of the seeds his family had been sewing for centuries.

One day, when he was much older, a grown man with children of his own, he received a notice by the Occupation forces, which told him his property was on unpermitted land, and he was to demolish his home and buy land elsewhere if he wanted to continue his agricultural practice. He had 3 days. Raed did nothing, he was paralyzed by the idea of having to abandon his home, the memories, and, secretly, what he feared the most was having to cut down his olive tree. Now he seldom climbed it to see Al Aqsa. He still hadn’t had the opportunity to visit her, but he knew she would wait for him and that she would always be there, visible from the “chair branch”, if he needed to peak at her.

No, he absolutely couldn’t abandon his land! His soil/soul. On the third day, a whole squad of soldiers showed up at his front door and informed him they were there to deal with the demolishment, since he hadn’t taken care of it on his own. Raed could not believe this was truly happening. He went back inside to talk to his wife and children, but as he was explaining the situation to them, the soldiers broke in and told him they had had enough time to deal with it, and were to leave now if they didn’t want to be demolished under their house too. The children started crying, his wife wailing, Raed was still struck, dumbfounded, incapable of knowing what to do, how to move on. They were shoved onto the street and told to take any valuables from the house before the squad started the operation. Within an hour, Raed’s whole history, feelings, life stories, were rubble, and his seeds, plants and trees, had been murdered and vanquished underneath the cement.

Raed’s family moved in with one of his siblings. For a whole year, Raed lived in a state of deafening depression. He would wake up every day and relive in his mind the atrocities which he witnessed in seeing every tile, brick, stoke of grass be subverted from its peaceful status.

Until one day, Raed woke up and decided he had to see Al Aqsa. He stood up, greeted with good mornings his family, and took the car keys. He took the road to Jerusalem, played music he had never listened to on the radio. He was now close to the checkpoint that led to Quds. There was little traffic. He could see the soldiers making fun of a young man on the side of the road, they had asked him to take his shirt off. Raed was driving quickly, he wasn’t thinking. He got closer and closer to the checkpoint, didn’t slow down. He drove and his foot had forgotten the brake pedal was there. Raed was now so close to the soldiers, he could see their terrorized faces as they watched his car crashing into them at a 100km/h.

Raed was killed instantly by two bullets in the head which made the car stop before he ran over more soldiers. The news that day reported a Palestinian terrorist was successfully neutralized during an attempted massacre.

Raed’s family never knew what happened. They found in his wallet a folded note which read “The olives, the oranges, the pomegranates, my sea! Soon, we will be reunited”.

This story was inspired by someone whose family I met in the West Bank. Raed is a fictional name. The real person will spend the rest of his life in an Israeli prison. He was nearly 80 years old the morning he drove his car in the checkpoint.

Leave a comment